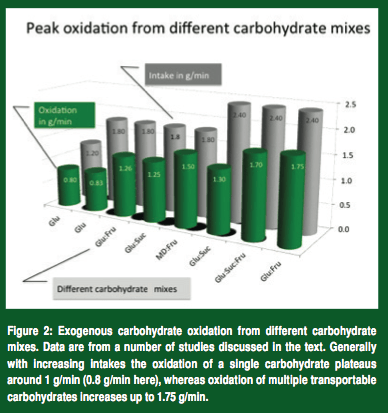

The ingestion of a combination of carbohydrates that use different intestinal transporters for absorption, carbohydrate delivery and oxidation can be increased. These increases are seen when a carbohydrate is ingested that uses SGLT1 for absorption and a secondary carbohydrate that uses a different transport system are ingested simultaneously. Increased oxidation is only seen when the SGLT1 dependent carbohydrate is ingested at high rates (1 g/min). Whereas previously it was believed that the maximum absolute oxidation rate of ingested carbohydrate oxidation was 1 g/min, recent studies with multiple transportable carbohydrates have reported values up to 1.75 g/min. The increased carbohydrate oxidation with multiple transportable carbohydrates was accompanied by increased fluid delivery and improved oxidation efficiency and thus the likelihood of gastrointestinal distress may be diminished. Studies have also demonstrated reduced fatigue and improved exercise performance with multiple transportable carbohydrates compared with a single carbohydrate. Therefore multiple transportable carbohydrates, ingested at high rates, can be beneficial during endurance sports where the duration of exercise is 2.5 h or more. Guidelines will have to be adjusted to take these findings into account.

REFERENCES

Bergström, J., L. Hermansen, E. Hultman, and B. Saltin (1967). Diet, muscle glycogen and physical performance. Acta Physiol. Scand. 71: 140-150.

Burelle, Y., M.C. Lamoureux, F. Peronnet, D. Massicotte, and C. Lavoie (2006). Comparison of exogenous glucose, fructose and galactose oxidation during exercise using 13C-labelling. Br. J. Nutr. 96: 56-61.

Cox, G.R., S.A. Clark, A.J. Cox, S.L. Halson, M. Hargreaves, J.A. Hawley, and L.M. Burke (2010). Daily training with high carbohydrate availability increases exogenous carbohydrate oxidation during endurance cycling. J. Appl. Physiol. 109: 126-134.

Currell, K., and A.E. Jeukendrup (2008). Superior endurance performance with ingestion of multiple transportable carbohydrates. Med. Sci .Sports Exerc. 40: 275-281.

Currell, K., J. Urch, E. Cerri, R.L. Jentjens, A.K. Blannin, and A.E. Jeukendrup (2008). Plasma deuterium oxide accumulation following ingestion of different carbohydrate beverages. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 33:1067-1072.

Ferraris, R.P., and J. Diamond (1997). Regulation of intestinal sugar transport. Physiol. Rev. 77: 257-302.

Hawley, J.A., A.N. Bosch, S.M. Weltan, S.D. Dennis, and T.D. Noakes (1994). Effects of glucose ingestion or glucose infusion on fuel substrate kinetics during prolonged exercise. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 68:381-389.

Hulston, C.J., G.A. Wallis, and A.E. Jeukendrup (2009). Exogenous CHO oxidation with glucose plus fructose intake during exercise. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 41: 357-363.

Jentjens, R.L., and A.E. Jeukendrup (2005). High rates of exogenous carbohydrate oxidation from a mixture of glucose and fructose ingested during prolonged cycling exercise. Br. J. Nutr., 93: 485-492.

Jentjens, R.L., L. Moseley, R.H. Waring, L.K. Harding, and A.E. Jeukendrup (2004a). Oxidation of combined ingestion of glucose and fructose during exercise. J. Appl. Physiol. 96: 1277-1284.

Jentjens, R L., M.C. Venables,and A.E. Jeukendrup (2004b). Oxidation of exogenous glucose, sucrose, and maltose during prolonged cycling exercise. J. Appl. Physiol. 96:1285-1291.

Jentjens, R.L., J. Achten, and A.E. Jeukendrup (2004c). High oxidation rates from combined carbohydrates ingested during exercise. Med. Sci. Sports. Exerc. 36:1551-1558.

Jentjens, R.L., K. Underwood, J. Achten, K. Currell, C.H. Mann and A.E. Jeukendrup (2006). Exogenous carbohydrate oxidation rates are elevated after combined ingestion of glucose and fructose during exercise in the heat. J. Appl. Physiol. 100: 807-816.

Jeukendrup, A.E. (2003). Modulation of carbohydrate and fat utilization by diet, exercise and environment. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 31:1270-1273.

Jeukendrup, A.E. (2004). Carbohydrate intake during exercise and performance. Nutrition 20: 669-677.

Jeukendrup, A.E. (2008). Carbohydrate feeding during exercise. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 8: 77-86.

Jeukendrup, A.E. (2010). Carbohydrate and exercise performance: the role of multiple transportable carbohydrates. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care, 13:452-457.

Jeukendrup, A. E. (2011). Nutrition for endurance sports: marathon, triathlon, and road cycling. J. Sports Sci. 29:Suppl 1, S91-99.

Jeukendrup, A.E., and K.D. Tipton (2009). Legal nutritional boosting for cycling. Curr. Sports Med. Rep. 8: 186-191.

Jeukendrup, A.E., and L. Moseley (2010). Multiple transportable carbohydrates enhance gastric emptying and fluid delivery Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 20:112-121.

eukendrup, A.E., and J. McLaughlin (2011). Carbohydrate ingestion during exercise: effects on performance, training adaptations and trainability of the gut. Nestle Nutr. Inst. Workshop Ser, 69, 1-12.

Jeukendrup, A.E., M. Mensink, W.H.M. Saris, A.J.M. Wagenmakers (1997). Exogenous glucose oxidation during exercise in endurance-trained and untrained subjects. J. Appl. Physiol. 82:835-840.

Jeukendrup, A.E., A. Raben, A. Gijsen, J.H. Stegen, F. Brouns, W.H.M. Saris, and A.J.M. Wagenmakers (1999). Glucose kinetics during prolonged exercise in highly trained human subjects: effect of glucose ingestion. J. Physiol. 515: 579-589.

Jeukendrup, A.E., L. Moseley, G.I. Mainwaring, S. Samuels, S. Perry, and C.H. Mann (2006). Exogenous carbohydrate oxidation during ultraendurance exercise. J. Appl. Physiol. 100:1134-1141.

Kellett, G.L. (2001). The facilitated component of intestinal glucose absorption. J. Physiol. 531: 585-595.

Leijssen, D.P., W.H.M. Saris, A.E. Jeukendrup, and A.J.M. Wagenmakers (1995). Oxidation of exogenous [13C]galactose and [13C]glucose during exercise. J. Appl. Physiol. 79:720-725.

Pirnay, F., J.M. Crielaard, N. Pallikarakis, M. Lacroix, F. Mosora, Krzentowski, G and P.J. Lefebvre (1982). Fate of exogenous glucose during exercise of different intensities in humans. J. Appl. Physiol. 53:1620-1624.

Rodriguez, N.R., N.M. Di Marco, and S. Langley (2009). American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Nutrition and athletic performance. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 41: 709-731.

Rowlands, D.S., G.A.Wallis, C. Shaw, R.L. Jentjens, and A.E. Jeukendrup (2005). Glucose polymer molecular weight does not affect exogenous carbohydrate oxidation. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 37: 1510-1516.

Rowlands, D.S., M.S. Thorburn, R.M. Thorp, S. Broadbent, and X. Shi (2008). Effect of graded fructose coingestion with maltodextrin on exogenous 14C-fructose and 13C-glucose oxidation efficiency and high-intensity cycling performance. J. Appl. Physiol. 104:1709-1719.

Rowlands, D.S., M. Swift, M. Ros, J.G. Green (2012). Composite versus single transportable carbohydrate solution enhances race and laboratory cycling performance. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 37: 425-436.

Triplett, D., J.A. Doyle, J.C. Rupp, D. Benardot (2010). An isocaloric glucose- fructose beverage’s effect on simulated 100-km cycling performance compared with a glucose-only beverage. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 20:122-131.

van Loon, L.J., A.E. Jeukendrup, W.H.M. Saris, and A.L. M. Wagenmakers (1999). Effect of training status on fuel selection during submaximal exercise with glucose ingestion. J. Appl. Physiol. 87:1413-1420.

Wallis, G.A., D.S. Rowlands, C. Shaw, R.L. Jentjens, and A.E. Jeukendrup (2005). Oxidation of combined ingestion of maltodextrins and fructose during exercise. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 37:426-4

Link: https://secure.footprint.net/gatorade/prd/gssiweb/pdf/108_Jeukendrup_SSE.pdf